The Animal Forms in Tai Chi

We are indebted to Andrew Moore who was taught by Master Moy and who is an Instructor in the Canadian Academy. He has generously shared his time and knowledge to put together these articles on the Animal Movements and so pass on some of his considerable knowledge.

The principles of our Tai Chi internal arts and the methods of executing the moves are embodied in the five animal forms. These are Tiger, Leopard, Dragon, Snake and Crane.

They are described as forms because they represent abstract aspects of our Tai Chi such as bone strengthening, tendon changing, turning/spiralling movements and gathering energy. One or more animal forms might be involved in any given move. We will start by looking at the Tiger.

The Tiger

The Tiger’s strength is in its bones. It represents power and strength. If we watch it move we will see it crouches to maintain a low centre of gravity (Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon anyone?) This gives it balance, strength and stability. It moves effortlessly in this way because its bones are strong.

Our practice of the foundation exercises the Tor-Yu and Dan-Yu both exercise and strengthen the leg bones in a Tiger-like form.

In the Dan-Yu we push down through the feet as we sit and also as we stand (slowly) back up again. The weight drives down through the bones and this compresses and constricts the leg bones which, as we rise, then relax back and expand. This compression and recoil create a pumping action for blood and helps build and improve the circulation to the bone marrow.

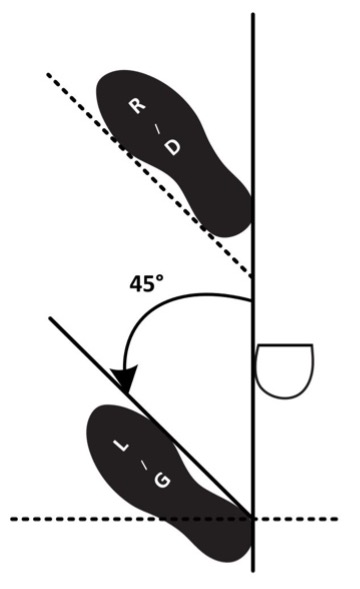

So too in the Tor-Yu where the weight goes down into the front leg and then transfers to the back leg. The weight is pushed down at the back of the Tor-Yu through the foot at 45° and then transfers into the front foot which is at 90° as we shift forward and complete the stretch. The stretching force creates a load on the bones of the straight leg so that both legs are equally worked in both the front and back positions of the Tor-yu. The stretch plays an equally important role in engaging the Tiger. It is important to maintain a solid connection of the feet to the ground in the straight leg to pump the circulation in both legs. At the back of the move the weight is sensed to be mostly into the back foot, at the front of the move it is in the front foot.

As with the Dan-Yu the weight compresses the load bearing leg and is then transferred into the other leg. The loaded leg is compressed whilst the unloaded leg expands back again creating a pumping cycle.

As we enter the Year of the Tiger, we should aim to have an awareness of our weight placement, loading the requisite leg correctly and understanding how this enables us to maintain a low centre of gravity and to build stronger bones.

The Leopard

Continuing our series on the animal forms in Tai Chi, #2 is The Leopard.

Leopards are magnificent creatures full of strength and agility. In their natural surroundings we can observe their grace of movement and beauty of colouring. They are fearless and daring. Their independent trait is something we can admire and they can teach us not to be intimidated by anyone or anything.

Speed, Spring, Leap.

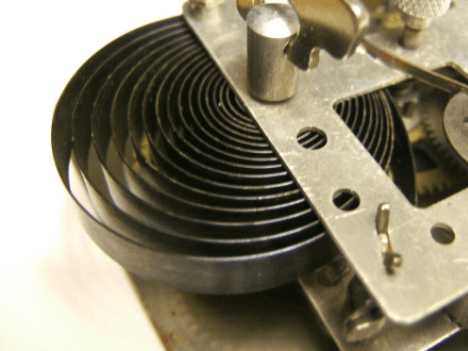

The speed comes from the ability to spring and leap. Think of a cat waiting and watching its prey, ready to pounce. We see it curl its body just like a clock spring being wound up as it readies to release the energy into, well, a spring forward. By coiling the tendons it has a store of energy that on its sudden release gives it speed and also precision of movement (more clock analogies!)

For this to happen efficiently its tendons must be fully relaxed and flexible with real elasticity to maximise both the coil and the release – tight tendons will limit this process.

Leopards represent Tendon Training for us. We should aim to transform our rigid, stiff tendons to make them flexible and elastic.

The leopard is often said to be the trickiest form to illustrate with examples. Keep in mind that it is about the tendons being flexible enough to give speed and strength through elasticity.

The Leopard in the Tor-Yu

The simplest example is allowing for freedom of movement of the arms in the tor-yu – a move which apparently Mr Moy commonly complained was being done: ‘Arms too slow’.

We frequently see people move forward as one unit instead of separating the body and having parts move independently. One part is the arms. The arms need to be able to move forward quickly, independent of the rest of the body. This is the ‘Pounce’ of the leopard.

To achieve this the tendons must be relaxed, soft and supple. The muscles cannot be engaged – the strength comes from trusting the Tiger (bones) to support you while the arms ‘Leap’ forward.

There is also a coiling stretching at the bottom of the sit back in the tor-yu which must be released to start the pounce.

So, the first stage of the Leopard is to get the softness and freedom of movement forward of the arms without the body going forward.

The second stage is to work on the coiling and uncoiling which incorporates the other animals (crane, dragon, snake and tiger).

The Leopard in the Brush Knee

Consider also the forward direction of the brush knee. Think about the softness and freedom of movement forward, the coiling and uncoiling that provides the energy for the pounce and so doing lets us get a sense of what is meant by the parts of the body moving independently.

In the brush knee the back hand needs to move forward independent of the body. An example Mr. Moy used was to imagine your friend grabbing the hand going forward. Your friend is doing the hard work moving the hand forward with little effort on your part. The hand moves freely, softly and without any force from the body pushing it away.

The sensation of being pulled forward is an aspect of The Leopard as the tendons are engaged and the joints open as the hand moves further and further away.

The body needs to stay balanced on the back foot (tiger) until the pull of the hand going forwards begins the weight transfer from back foot to front foot.

While the leopard is engaged going forward (hand/arm) the remainder of the body is engaged in the uncoiling of the spiral turn from the back foot up to the top of the head. This is an upward direction not a forward direction – that is what is meant by parts of the body moving independently.

Once the turn reaches the top of the head on the rise it begins the descent as a spiral down into the front foot – there is very little forward movement of the body. The forward direction obtained is a function of the Leopard movement and the shift of energy in the body.

To set up The Leopard the coiling needs to be engaged during the sit of the brush knee to store energy in the tendons which can be released as part of the ‘Pounce’ forward.

#3 Dragon Movement in Tai Chi

Dragons are said to be animals with very flexible spinal columns. Looking at images of dragons it would appear that their entire body is a spinal column. If you have ever seen a dragon dance you will see that the dragon can curl its body into concentric circles, unwind and become a long, straight line. The contraction and expansion can only be achieved by having an elastic spinal column. The elongated body of the dragon describes the spinal column.

The spinal column’s elasticity is a result of the movement of every single vertebra. We are now told that there is movement in the sacral area (found at the bottom of the spine between the fifth segment of the lumbar spine and the coccyx/tailbone (L5 down to L1) which was previously thought to be unmoveable. While there is movement in the vertebrae fusion in the discs will not occur. The movement allows spinal fluid to flow through the spinal column and circulate in the body.

There are many different ways to look at the dragon which can be found in many of the Tai Chi movements.

The dragon is typically associated with the expansion (stretch) and contraction of the body.

We will deal with each of these in separate articles and then show the Dragon movement in a specific Tai Chi move in a further post.

The first is the expansion/stretch.

One of the interesting aspects of the stretch is utilizing the ‘stored energy’ or ‘returning force’.

When you stretch and open and then return this is a very effective pump that moves the circulation to every part of the body and returns the circulation back to the centre.

One of the key aspects of accessing this stored energy is that it is stored in the elastic structures of the body.

As the body becomes more elastic there is more energy that can be stored in the stretch.

This energy can be stored in the joints, the spine, the tendons and other parts of the body.

Typically the stretch is engaged as part of the turning or spiralling either in the rising or falling direction.

Also, some parts of the body can be expanding while other parts are contracting.

In order to access the expansion, the body must relax. A body that is using muscles to move is a body in contraction which cannot stretch.

When the movements are initiated by the turn of the spine the muscles are not involved and the strength of the form comes from the bones and not the big muscle groups.

For most people the stretching aspect is the first part of the dragon that is experienced.

You cannot access the return if you don’t first expand.

So the stretch is the first priority – to begin to engage the stretch through relaxing and turning.

Mr. Moy’s Tai Chi set incorporates a safe path to start people on stretching if they have a solid understanding of the angles and directions of the movements of the set.

As people progress from one move to the next they should practice the turning and the other five basic principles which will begin opening the body.

Learning to let go is the path to opening the body. Forcing the body to stretch will result in discomfort and potentially injury.

The second aspect is to access the returning force / contraction of the dragon.

This energy can be used to initiate the next move in the sequence, again reducing our dependence on using the big muscle groups to initiate movement.

Like the expansion, the return cannot be accessed if the large muscle groups are engaged. The moment the movement engages the muscles the return force is lost.

If you think of a spring that is coiled up in its ‘resting’ state it is neither expanded or contracted.

When a force is applied to pull the spring apart or compress the spring, the shape of the spring changes and the force applied is stored as potential elastic or spring energy.

When the force is released, the spring uses the stored energy to return back to its resting state.

The key here is to release the force of the stretch in a way that allows the return from the stretch to move the body in a balanced and relaxed way.

When you apply the force to stretch and release the force to return, it is important to understand the direction of the forces and the anchor points of the stretch.

These anchor points are how you maintain connectivity and smoothness to the movement. The moment an anchor point is lost, the stretch or return will disappear.

Mr. Moy called these anchor points ‘The Five External Harmonies’ = The two tigers mouth, The two bubbling springs and the Point of Hundred Gatherings. (The Point of a Hundred Gatherings is also known as Bai Hui and is on the uppermost point of our body, the centre of the top of our head. It’s the place where all of the energies of our body meet making it one of the most powerful points on our body.)

When these points maintain harmony a move is connected and the five animals can be accessed.

These five points are basically where the body connects to the external world and are the boundary between the inner and outer universe.

It is key when stretching and even more important on the return to maintain balance between the five points.

The brush knee is an excellent tool to play with understanding the return force.

When you stand up in the brush knee you want to set up the balance so that you can sit down in a way to store elastic energy.

This can be stored in all of the ball joints as they rotate while sitting, as well as the tendons that can be engaged in opening the body.

On the sitting, encourage people to sit low but to also expand through their chest to connect the two tigers mouth to store energy in not only the vertical direction but also in the horizontal direction (and rotational directions in the ball joints).

The next challenge is to use the stored force to initiate the turning of the brush knee in the vertical rise without engaging the strong muscle groups (especially the strong thigh muscle).

If you release the stretch in the arms when the turn is initiated the movement of the arms can be done using the stored energy without any extra muscular force.

Key to releasing the stretch is to drop the elbows of both arms.

If people can ‘let go’ and allow the return from the stretch to bring the hands to the front of the body ready to do the brush knee (down and out), they will experience a lightness and softness to the movement.

Likewise, if you can maintain balance on the back bubbling spring during the spiral up, the rise and turn will happen without effort utilizing the stored energy.

Be very careful that you do not shift forward when the turn is initiated. This is usually a sign the turn is not centred and is applying harmful forces to the bending knee.

This gets us to what Mr. Moy called the ‘turn balance point’ where we start the next dragon as we begin the descent into the front foot in the brush knee.

In the forward direction we want to stretch the tendons (back heel to front hand, etc.) and store energy in the rotational forces in the ball joints as we sit down in the front foot.

Again this is achieved with the spiral turn down in the front dan-yu without the use of the large muscles. Key is the relaxation into the floor (including relaxing the front of the body) and maintaining the harmony between the five points.

The stored energy in the forward direction can be accessed to be used to initiate the twist-step and rise to return to the standing position to start the process again.

Hopefully the brush knee will have a sense of expansion and contraction which is the dragon.

The less effort or muscular force that is used in the brush knee will result in a soften and more elastic movement.

The same concepts can be applied to the moves of the set.

Start by identifying the dan-yu and spiral turns.

Work on sitting to open the body and improve bone strength.

Make sure the direction of movement is following the guidelines from Mr. Moy for each move.

Work on connecting the five harmonies and maintaining the connectivity throughout the movement.

Finally work on letting go. This is the path to moving meditation and a complete exercise for both body and mind.

#4

Continuing our series on the animal forms in Tai Chi – a look at Snake Movement

The early development of Tai Chi by Chang San Feng (張三丰) was based on mimicking the movements of animals in nature.

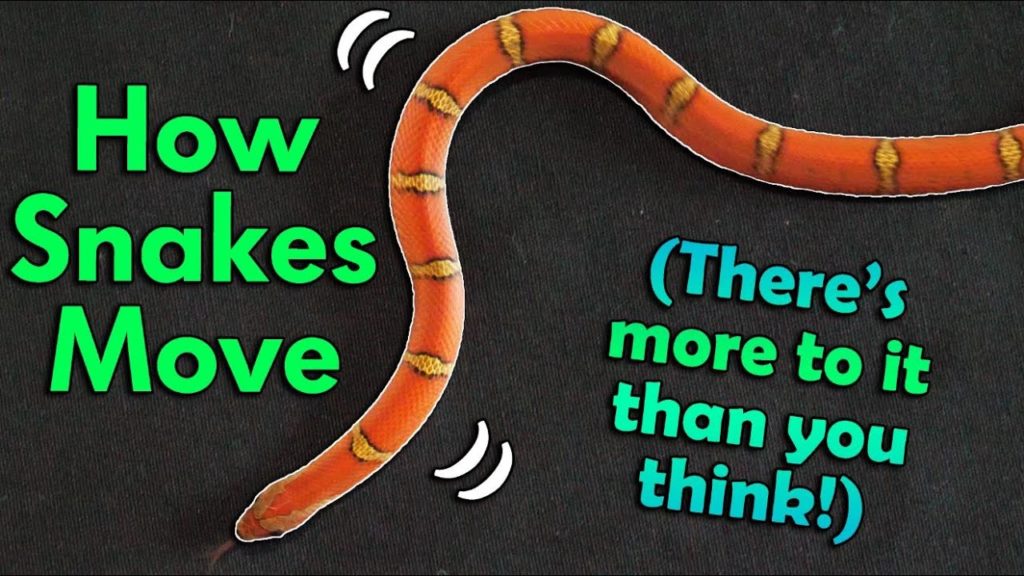

The movement of the snake is typically associated with the side-to-side movement when looking down at a snake moving across the ground.

This is a common movement in the Tai Chi set when there is a transfer of weight from one foot to the other.

One example is the transition from Step Up Raise Hands into Stork Cools Wings.

The weight shift from Left To Right (shown in figure) is done without turning (parallel step).

The rising and falling aspect of the Tiger animal is present as the weight transfer is accomplished with a standing up on the left leg and a sitting down on the right leg.

One important aspect of the weight shift is to maintain a connection between the back (left) foot Bubbling Spring and the Tiger’s Mouth in the top (left) hand. When the back leg has finished straightening and the top arm has finished straightening the weight transfer should be completed with the sitting down into the right foot.

The Snake animal is also associated with the movement of the lower vertebrae (lumbar).

The shape of the vertebrae and the connections between the bones allows for a range of motion from side to side.

As you travel up the spine the side-to-side mobility of the spine decreases.

Mr. Moy spoke about Tai Chi movements being initiated by the coccyx and then progressing up the spine (on movements that start low and go higher).

So we often associated the start of a turn as being initiated by the Snake animal and supported by the other animals.

When we sit back in a move like Grasp Bird’s Tail one of the goals is to open the pelvis and separate the SI joints at the back.

The opening of the pelvis allows the Snake animal to be engaged allowing the base of the spine to turn to begin the going up and forward aspect of the move.

If the sit bones have not dropped, the pelvis is closed and the Snake is lost.

If the bones have not been stacked, the alignment is lost and the Dragon is lost.

If there is tension in the body and the muscles are engaged how can the circulation move through the body?

The softness of Tai Chi is important in all moves to engage the tendons and the bones.

By starting the turn at the base of the spine, the turn travels in two directions

– towards the top of the head (Point of Hundred Gatherings / Bai hui 百會)

– towards the foot travelling down the leg into the foot (Bubbling Spring)

To achieve the two directions, all of the animals need to be coordinated and work together.

If you use the strong muscles of the back leg to initiate the movement, the animals are lost.

If you lose the balance and shift forward, the animals are lost.

Maintain the quiet of the Crane, trust the Tiger (bones), relax to initiate the Leopard (tendons), access the contraction of the Dragon to stand up engaging the elastic structures that have been stretched.

The movement from back foot to front foot is initiated by the Snake.

White Stork Cools Wings is a very good movement to practice to learn to initiate the movement from the turn at the base of the spine.

At the start of the move, the weight is dropped into the Bubbling spring of the right foot.

When the left foot steps in empty, it is critical that the weight remains down in the foot.

The rising does not begin until the empty step is made with the left foot.

The right leg must remain relaxed and allow the turn to do the work to bring the body up tall without effort.

Use the empty step to help with balance but do not allow the balance to change – the balance needs to remain in the right bubbling spring.

Try to get the sense of the turn progressing from the base of the spine up each vertebrae to the skull.

There will also be a rotation downwards towards the bubbling spring as the angle of the body rotates through the 45 degrees.

There is also rotation in the ball joints of the hips and ankle and bones of the right leg.

The spiral turn winds sections of the body and unwinds other sections of the body.

The turning of the spine engages the internal organs to gently move and massage them.

Using the muscles to initiate the movement the organs become ‘stuck’ and often are compressed instead of gently massaged.

The snake is a critical element in almost every move to achieve a whole body exercise..

We will examine the Snake animal in two of its manifestations.

The Snake in the Tai Chi context is associated with a style of movement where the weight is shifted without the spiral turn.The snake movement is a weight shift (may have an up and down component) without a change in the angles of the body.

The Lok Hup set contains numerous examples of this type of snake movement.

The Tai Chi move 45 “Right Foot Kick” is a good example of the snake movement.The move starts with a twist step, stand-up and kick followed by a sit on the same foot at the angle of the foot (45 degrees).It is interesting to play with the kick as a Dragon exercise to experience the expansion of the kick followed by the contraction into the sit.The right foot should step empty at a 45 degree angle (parallel step). The body level remains in a sit.The next part is the weight shift from the sitting foot (left) to the right without turning remaining at the level of the sit (no up or down component during the transfer).Once the lateral shift is complete, you should stand tall on the right foot pointing to heaven connecting the earth (bubbling spring on the right foot) to heaven with the right leg fully straightened.Notice that the body angle does not change through this sequence.This will set up the beginning of the strike tiger by dropping into a low sit on the right (body angle is at 45 degrees) with an empty step with the left at the bottom of the sit.

Another example of the snake is within move 6 “White Stork Spreads Wings”.Once the body turns left and sits to complete the ‘hold the ball’ the body is facing the 45 degree angle lined up with the left foot.The right foot should step empty at a 45 degree angle (parallel step). The body level remains in a sit.The weight transfer occurs from left foot to right foot with the body remaining at the 45 degree angle.It is recommended not to turn in this move to preserve the snake movement.For this move there is a rising and falling as the move starts with a rise on the left foot (connecting to the extension of the left arm).The move completes as the weight descends down in the right foot.The position of the right hand helps with the feeling of the downwards drop It is important that the balance is over the bubbling spring of the right foot with a strong connection through the left straight leg to the left foot bubbling spring.If the move has too much of a forward direction the balance is lost and the relaxation in the drop does not occur.We are trying to set up a low sit at the 45 angle for the rising turn of the stork spreads wings.The initiation of the rising turn (to spread wings) is also considered a Snake movement discussed next in the context of the Tor-yu.

Another perspective on the Snake movement in Tai Chi is associated with the turning in the coccyx, sacrum and first bones of the spine (lumbar region).This quality of the movement has a lateral component similar to the movement of a snake if watched from above with the snake’s side-to-side motion moving the snake forward.The vertebrae of the lower spine have a different structure compared to the vertebrae higher up in the spine (Thoracic and Cervical) and so the lower spine has a capacity to move laterally while the upper spine is designed for bending, stretching and rotation.The initiation of all turns in Tai Chi originates at the coccyx. It is critical to expand the pelvis so that the stretch opens the SI joint maximizing freedom of movement of the base of the spine.

A simple example of this movement is in the starting of the tor-yu in the upwards direction balanced over the back foot. The pelvis is opened during the drop / sit of the tor-yu expanding the SI joints as the internals relax and drop.The turning of the spine travels both upwards to the head (progressing through the spine) as well as downwards towards the back bubbling spring.The downwards rotation is along the axis of the back leg turning from the top of the femur (hip ball joint) down to the foot (ankle ball joint).The initiation of the turn from the low back begins the opening of the arms in the tor-yu and the straightening of the arms.As each vertebrae progressively turns there is a feeling of rising as the body rotates around the centre axis (the spine).The snake movement is initiating the turn with the support of some of the animals and allowing the appearance of the other animals.

#5 The Crane

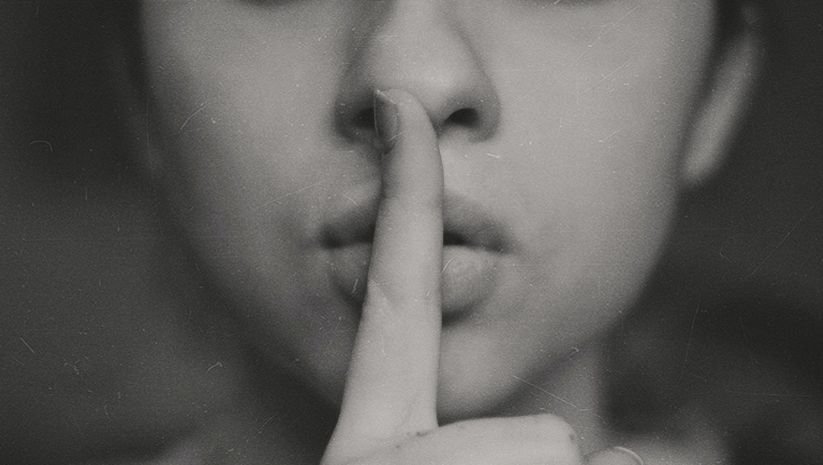

The image of a Crane standing in the water is the image of stillness. It looks for the movement of its prey but it stands absolutely still – the reflection of its image is a powerful indication of its complete stillness.

Apparently in the water the crane stands still and only moves its toes to attract fish which becomes its meal. The movement of the fish is what it looks for. At the root of Mr. Moy’s meditation tradition is the concept of stillness and emptiness also called quiet cultivation.The goal of all the meditation and movement practices is to achieve stillness and emptiness – having no thoughts.

There is both a physical and mental aspect to the Crane.

The mind in Traditional Chinese Medicine is associated with the Monkey – the Monkey Mind.

The Monkey Mind is a busy mind that is always active, busy thinking and being distracted by the surrounding world and inner thoughts.

A move like “Step Back to Ward Off Monkey” refers to how the Tai Chi practice can help to regulate thoughts. The move helps to still the mind to quiet the Monkey. The move exercises the physiology which also works the mind – the dual cultivation of body and mind. The Ward Off aspect has a martial application to keep an opponent away while stepping back. The stretching and turning in the move stimulates the movement of the cerebral spinal fluid which brings circulation to the brain. The circulation to the brain will aid in the relaxation of the mind.

When we first arrive to attend class, our minds are busy with the concerns of the world – remember to pick up items at the grocery store, concerns about friends and families, etc. The act of practising Tai Chi begins the process of letting go of those concerns. Within a very short amount of time the worries dissolve and for the duration of the class the body benefits from the quietness of the mind.

At the end of a set we do standing meditation to enjoy the sense of well being and to ‘recharge’ the batteries after the hard work of the class. There are many studies on the benefits of meditation on your health. Western science talks about how when your mind is active working on problem solving and thinking thoughts the brain consumes energy and is stimulated. The meditation practice allows the brain to rest and the energy is conserved and can be utilized in the body in other ways (like healing itself). The meditation will also influence the hormones circulating and nervous system which can affect every part of the body.

The Crane in our Tai Chi movements can be seen as ‘Balance’ and a quality of movement. When we first start learning Tai Chi our mind is busy learning the set – where the hands go and where the feet go. Eventually we start learning the ‘in-between’ parts of moves as we go from the start of a move to the next move. With repetitions the mind will not work as hard so the movement becomes automatic.

Mr. Moy would often tell the group ‘You are not thinking’ – telling us that we are not following the instructions and working on the concept he introduced. A short time later Mr. Moy would than tell the group ‘You’re thinking too much!’ – once you have practiced it is time to let go and allow the movements to happen (integrating the new concept into your moves).

In the set we have a Crane – “White Stork Cools Wings” which on the outside reflects the shape of a Crane. On the inside of this move it is important to achieve stillness during the rising and falling. The spiral up and spiral down must be done in a balanced way so that the centre does not move from the bubbling spring of the right foot. The upwards movement starts with stillness as the left foot steps in to the half step. The body does not move on the step with the balance established over the bubbling spring in the right foot. The rotation of the spiral is around the spinal axis in the vertical alignment so that the centre is still. This same sense of balance of the up and down without movement can be seen in many moves of the set.

An example is in the standing up and sitting down of the Brush Knee over the forward foot. The move has a spiral up on the forward foot (bubbling spring) followed by the drop down into the bubbling spring. The balance does not move so that there is no shifting forward or back during the rise and fall. The key to this balance is learning to let go and to trust the strength of the body (Tiger) and flexibility of the joints (Leopard) and the movement of the spine (Dragon). The transfer of the weight from back foot to forward foot in the Brush Knee also has a Crane element. When we first practice our Brush Knee we move forward quickly so that we release the work on the sitting leg and move forward. It takes time to strengthen the body and to improve the flexibility of the joints – this is called Building the Foundations. As the body changes with the bones strengthening and the elasticity of the tendons increases, we can be more patient and not rush forward but keep our balance on our back foot for longer. The 45 degree rotation of the Brush Knee is around the centre axis (spine) which is the Crane balance. The body needs to have a vertical orientation balanced over the back foot (bubbling spring) without leaning forward or moving forward. The Tiger and Crane need to be established at the start of the forward movement to allow for the other animals to make an appearance and play a role in the movement (Snake, Leopard and Dragon). To maintain the stillness within the Brush Knee, it requires patience in the movement and trust in the physiology and the letting go both inside and in the mind. The Crane starts when we begin the set by standing still before we bow and remains until we complete the final bow – the Tai Chi set is moving meditation.

Mr. Moy would have the group walk around the room after completing the set to ‘return to the real world’. This is to allow time for the Crane to complete and the mind to become more aware of the surroundings. There are also circulations that continue in the body after the set is complete which also need time to settle. The sense of well being after you complete the set is a reflection of the meditative practice of Mr. Moy’s Tai Chi. Ultimately Mr. Moy talked about the ‘Grand Ultimate’ how you can do Tai Chi all day while you walk (move), stand, sit and sleep. This reflects having the ability to have the Crane and the energy circulation happen during your regular activities.

Understanding Movement In Tai Chi – Extending The Discussion Beyond Single Animal Forms

The sixth of the twelve year cycle of animals in the Chinese zodiac. Historically serpents and snakes represent fertility or a creative life force. They are a symbol of rebirth, transformation, immortality and healing because they shed their skin.

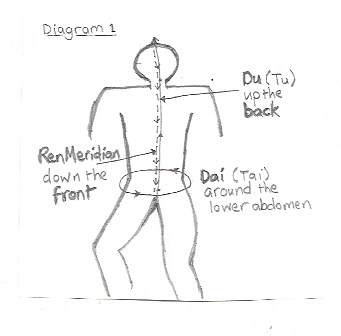

Like the dragon the snake’s body is elongated and they travel in a zigzag manner – a wave moving down the spine when seen from ahead & above. This motion is achieved by turning of the spine. The snake represents spinal training focused on turning. The base of the spine is the fulcrum (the point about which the pivot rotates) for this motion of the spinal column. This motion results in the circular movement of the internal organs. This turning helps to loosen the gates on the Du/Tu meridian. It can release the blockages on the Dai Tai meridians which circle around the lower abdomen.

When we have snake and dragon combined we get expansion and contraction of the spine as well as turning. These two movements work together to produce a spiral motion with upwards and downwards movement along with rotation. The result is a massaging of the internal organs in a spiral manner which stimulates the respiratory, endocrine*, immune and digestive systems. Snake and dragon forms are seen in the increasing control and then easiness of the stretching, sitting and turning. So in effect we see the stretch becoming the consequence of the sitting and vice versa. In addition the movement achieves an element of unconscious reflectiveness.

We are very grateful to Andrew Moore, CTCA, for these pieces

*Endocrine System

A complex network of glands (eg. pituitary and thyroid) and organs (eg. kidney and heart). It uses hormones to control and coordinate the body’s metabolism, energy level, reproduction, growth and development as well as response to injury, stress and mood.

The Three Gates

This refers to the three Dan Tiens in the front of the body. In new born babies the gates are open. As a result of our journey through life, injuries and not taking care of our body and mind we have closed these gates. If the gates are not open then Chi cannot circulate properly. The meridian network is hindered because meridians pass through the gates. The theory in traditional Chinese medicine is that when these gates are open Chi can freely circulate and that is really important for the maintenance and recovery of health.

Many exercises in Tai Chi are focused on opening the three gates. Opening the gates corresponds with a straightening of the spine so as to open the gates the spine needs to be elastic with the freedom of movement in each of its sections. The elasticity functions as a pump to transport the chi from the Bai Hui (top of the head) to the lower gate (at the tailbone). If the lower gate is not open chi will have trouble going through this gate and there will not be what is termed the Grand Circulation which means the chi cannot fully nurture the legs.

The middle gate is positioned behind the heart and between the should blades where the spine connects to the arms via the scapula (ie. the should blades). If this middle gate is not open when the chi reaches this area travelling up the spine then full chi circulation will not be achieved because it will not flow out through the arms.

The upper gate is where the spine connects to the head. This gate connects the back to the top of the head and thence to the front and also a gate to the upper dan tien. This dan tien has no exact location according to some older Taoists but it is believed to be somewhere in the head. More recent thoughts on this dan tien think of it as a point equal to what is called the ‘Third Eye’.

The Three Treasures

When the gates are open the three dan tiens will be active and accumulating and transforming the three treasures. Each of the three contribute to the health and longevity of a person’s life. They are:

- Jing (essence). Jing is the essential foundation of your health. Think of it as a candle itself – Jing is the quality and quantity of the wax.

- Chi (energy/breath). Chi is the energy that courses through the body. Think of this as the burning flame of the candle.

- Shen (spirit). Shen is your spirit – it is all about enlightenment and illumination – the light produced by the candle’s burning flame.

So we see that the three treasures are the essence, energy and spirit of a person which are essential for sustaining a long and healthy life.

Bai Hui.

The Bai Hui is also known as The Point of a Hundred Gatherings. It is found on the uppermost point of the head. It’s the place where all of the energies of our bodies meet making it one of the most powerful points on our body.

Meridians

As we continue to look at some of the theory behind our Tai Chi – the animal forms etc. – we should also consider The Meridians, Gates, Dan Tiens, Bai Hui and The Three Treasures. These all have their basis in Chinese medicine and lie behind some of the forms, stretches and moves we do.

The Meridans are not real anatomical structures. Rather, in Traditional Chinese Medicine they are the pathways through which chi (energy) flows – it is seen as a channel network.

The Meridians start at the coccyx (base of the spine) and move up the spinal column then over the head to descend down the front of the body.

The base of the spine is a pivot for this motion of the turning of the circular movement of the internal organs. This turning also helps to loosen the gates on the Du/Tu Meridian. It can release blockages of the Dai/Tai Meridian which circles around ourn lower abdomen.

The Dragon as discussed earlier represent the training of elasticity in the spinal column – expansion and contraction spinal. This promotes health benefits. Vertebrae movements stimulate spinal fluid circulation. The spine is the path of the Du/Tu Meridian with its three gates. Dragon movement is key to opening these gates.

The essence of training the dragon is the balance between the contraction and expansion

Note: Not sure that is the Dragon Training we are discussing here….

We are told that Mr Moy expressed this concept as ‘Stand Up, Sit Down Same Time’.

Think of executing a Dan Yu . Spiral stretching is achieved by engaging the Dan YU at the start and end of each movement. This engages the stretching in the tendons throughout the body. The contraction is associated with elasticity of tendons in the body.

Joan Hodgson